Scheuermann’s Kyphosis (SK):

Incidence:

- 1-10% prevalence in adolescent population.

- Rare in patients under 10 years.

- Associated conditions:

- Spondylolysis – occurs in 6% of population with SK and scoliosis.

- Scoliosis occurs in 25% of population with SK.

Demographics:

- Usually detected at puberty in skeletally immature adolescents.

- Males are twice as likely to develop SK than females;

- Can be dismissed as poor posture, which can delay diagnosis;

- SK patients have an increased risk for elevated BMI:

- Clinical diagnosis may be delayed in patients with higher BMI.

Symptoms:

- Compensatory hyperlordosis of lumbar and cervical spine;

- Tightness of hamstring tendons;

- Patients complain of pain at apex of kyphosis in neck, upper back or lower back.

Genetics:

- Autosomal dominant inheritance patterns

- High penetrance and variable expression.

Diagnosis:

- Scheuermann’s Kyphosis is a rigid spinal kyphosis in thoracic/thoracolumbar region.

- Kyphosis may be increased in magnitude (> 50°) or may have an abnormal apex location in the lower thoracic or upper lumbar spine with smaller kyphosis magnitude.

- Thoracic Kyphosis > 45°; normal range is 25-40°.

- Thoracolumbar kyphosis > 30°; thoracolumbar spine is normally straight.

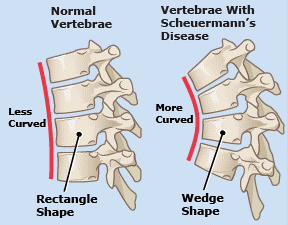

- Anterior wedging of greater than 5° in three or more vertebrae.

- Disc plate narrowing.

- Endplate irregularities.

- Schmorl’s nodes.

Disk wedging and irregular plates:

Symptoms/Associated Findings:

- The distinction between poor posture and Scheuermann’s Kyphosis is that the Scheuermann’s curve is much more rigid and the Hyperkyphosis doesn’t reverse with hyperextension.

- Rounded back.

- Back pain located over apex of kyphosis.

- Back pain involving lower lumbar spine when excessive lordosis is present.

- Non-radiating pain.

- Physical disability.

- Decreased range of motion/strength in back.

- Restrictive lung disease with curvature greater than 90°.

- Hamstring tightness.

- Scoliosis.

- Lumbosacral spondylolisthesis.

- Disc degeneration.

- Decreased participation in athletic activity.

- Increased BMI is correlated with kyphosis magnitude.

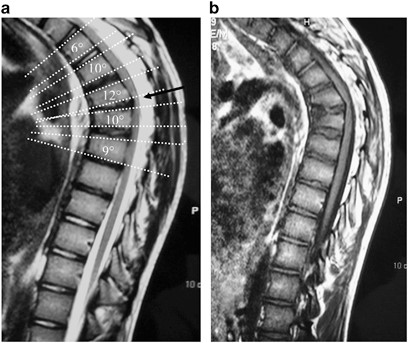

Radiographs:

- Lateral standing view required for diagnosis.

- Lateral x-ray with the patient hyperextended over bolster demonstrates the degree of stiffness of the curve.

- Apex of the deformity is most commonly in the thoracic spine, often lower (T7 or T8) than the normal thoracic apex of T6 or T7.

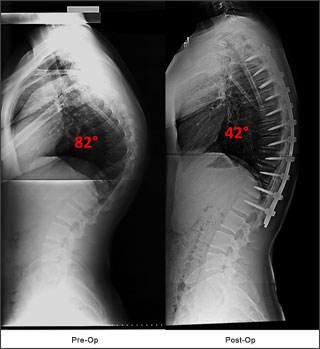

This is a case of Scheuermann’s Thoracolumbar Hyperkyphosis treated by posterior spinal fusion with pedicle screws and rods.

Note the kyphosis has been reduced 40 degrees and there is a decrease in compensatory upper thoracic and lumbar hyperlordosis following surgery.

The low apex was normalized to the mid-thoracic spine following surgery.

The patient below had a mid-thoracic hyperkyphosis. Harmonious restoration of the kyphosis to the high normal range was performed to match the patient’s pelvic incidence and PJK was avoided.

- MRI used if neurological findings present during exam.

- Also recommended for all operative patients to evaluate for:

- Endplate irregularities;

- Disc herniation of variable degree often noted which may require removal if compressing cord or nerve root;

- Schmorl’s nodes;

- Vertebral body wedging.

Treatment Options Past and Present:

- Treatment is dependent on kyphosis magnitude, skeletal maturity, pain severity, neurological compromise and self-image concerns.

- Non-operative Treatment:

- Young adolescents with kyphotic deformity < 55° and no evidence of progression may be observed.

- Brace treatment:

- Reasonably successful in preventing progression in skeletally immature patients – correction of deformity often attainable.

- Helpful with pain management.

- Bracing criteria – angles between 55-70°.

- Angles greater than 70° respond less favorably.

- Regimen – 18-20 hours per day for 12-18 months or until a reversal of vertebral wedging is noted.

- Brace with anterior flanges to shoulders is required for thoracic curves even if patient has no pain.

- Standard TLSO for curves below T8.

- Rigorous exercise and stretching:

- Strengthen endurance by emphasizing thoracic extension.

- Helpful with bracing.

- Helpful for control of kyphosis in less rigid deformities.

- May prevent excessive lordosis and hamstring contractures.

- Majority of patients are successfully treated non-operatively.

- Operative Treatment

- Surgical management utilized:

- Curve is greater than 75 degrees;

- If thoracolumbar kyphosis is greater than 30°;

- Neurologic deficit;

- Refractory pain;

- Unacceptable self-image;

- Curve is progressive despite bracing;

- Most cases are amenable to correction from an all posterior approach.

Anterior surgery needed to remove discs herniated into the spinal canal.

- Goal of surgery:

- Alleviate pain.

- Correct deformity within normal range taking pelvic incidence into account.

- Cobb end vertebra should be included in the proximal fusion to avoid Proximal Junctional Kyphosis (PJK) (see below for discussion of PJK).

- Restore global sagittal alignment.

- Prevent progression.

- Historical surgical technique:

- Harrington compression instrumentation.

- Hook and rod systems example: Cotrel-Dubousset (CD).

- Combined anterior and posterior surgery to avoid pseudoarthrosis, rod breakage and loss of correction prior to pedicle fixation.

* There is a higher rate of complication associated with a combined approach.

- Posterior-only operation with fusion and compression:

- Pedicle screw or hybrid instrumentation utilized.

- Relief of back pain and spontaneous correction of lumbar hyperlordosis noted.

- Most patients amenable to all posterior correction.

- Correction with multi-level posterior column osteotomies at the apex of deformity.

- Advanced three column osteotomies or combined anterior-posterior surgery may be necessary for very severe and rigid deformity.

- Thoracoscopic anterior surgery reduces morbidity from open thoracotomy performed in the past.

- Thoracic disk herniation:

- Acute paresis during correction.

- MRI required in setting of large posterior disc herniation.

- Discectomy performed usually from an anterior approach to avoid paralysis during corrective surgery.

- Surgical management utilized:

Complications:

- Kyphosis greater than 90° can affect pulmonary function.

- Progressive condition could lead to pulmonary failure in only severe cases.

- Patients with more severe curves should be monitored for pulmonary function preoperatively and postoperatively.

- Major complications are 3.9 times more likely to occur in operative SK than in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS).

- 14% complication rate in operative SK.

- Surgical site infection and neurological complications are more common.

- SK has a higher risk for reoperation than AIS.

- Instrumentation failure (hook or screw pull out) post-surgery.

- Development of proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK) after surgery common:

- PJK: Kyphotic angle above the instrumented spine to the first level of instrumentation that is at least 10° greater than preoperatively.

- Occurs in up to 1/3 of patients.

- Presence of PJK is often asymptomatic, but when severe can be painful and unsightly.

- Most common source of PJK is improper selection of the upper instrumented vertebra. It is also due to mismatching of the kyphosis correction to the patient’s innate sagittal curvatures determined by pelvic incidence.

- When PJK occurs, its magnitude directly correlates to magnitude of pelvic incidence.

Outcomes:

- Patients with SK have significantly lower scores in all domains on the Scoliosis Research Society Questionnaire (SRS-22) than in AIS and normal adolescents.

- VAS (pain score) in the SK population correlates negatively to pain, self-image and mental health domains of the SRS-22.

- Increasing kyphosis magnitude has been correlated most strongly with worse self-image.

- Thoracolumbar kyphosis apex in SK had greater association with pain than thoracic kyphosis apex at T7, T8, T9.

References

- Abbi G, Lonner BS, Toombs CS, Sponseller PD, Samdani AF, Betz RR, Shah SA, Newton, PO.Preoperative Pulmonary Function in Patients with Operative Scheuermann Kyphosis . Spine Deformity. 2014;2(1):70-75.

- Ascani E, Salsano V, Giglio GC. The incidence and early detection of spinal deformities. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1997;3(1): 111-117.

- Boseker EH, Moe JH, Winter RB, Koop SE. Determination of “normal” thoracic kyphosis: a roentgenographic study of 121 “normal” children . J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20(6):796-798.

- Bradford DS, Lonstein JE, Ogilvie JW, Winter RB. Moe’s Textbook of Scoliosis and Other Spinal Deformities, ed 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1987. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/8610904

- Clark CE, Shufflebarger HL. Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation for Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1994; New Orleans, LA.

- Coe JD, et al. Complications of spinal fusion for Scheuermann kyphosis: a report of the Scoliosis Research Society Morbidity and Mortality Committee. Spine. 2010;35(1):99-103.

- Geck M, Macagno A, Ponte A, Shufflebarger H. The Ponte Procedure: Posterior Only Treatment of Scheuermann’s Kyphosis Using Segmental Posterior Shortening and Pedicle Screw Instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20(8):586-593.

- Halal F, Gledhill RB, Fraser FC. Dominant inheritance of Scheuermann’s juvenile kyphosis. Am J Dis Child. 1978;132(11):1105-1107. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/717319

- Hosman AJ, Langeloo DD, de Kleuver M, et al. Analysis of the sagittal plane after surgical management for Scheuermann disease: a view on overcorrection and the use of an anterior release. Spine. 2002;27(2):167-175.

- Koller H, Juliane Z, Umstaetter M, Meier O, Schmidt R, Hitzl W. Surgical treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis using a combined antero-posterior strategy and pedicle screw constructs: efficacy, radiographic and clinical outcomes in 111 cases. Eur Spine J. 2014 Jan;23(1):180-191.

- Lee GA, Betz RR, Clements DH 3rd, Huss GK. Proximal kyphosis after posterior spinal fusion in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 1999;24(8):795-799.

- Lonner BS, Newton P, Betz R, Scharf C, O’Brien M, Sponseller P, Lenke L, Crawford A, Lowe T, Letko L, Harms J, Shufflebarger H. Operative management of Scheuermann's kyphosis in 78 patients: radiographic outcomes, complications, and technique. Spine. 2007 Nov 15;32(24):2644-2652.

- Lonner BS, Toombs CS, Guss M, Braaksma B, Shah SA, Samdani A, Shufflebarger H, Sponseller P, Newton PO. Complications in operative Scheuermann kyphosis: do the pitfalls differ from operative adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Spine. 2015 Mar 1;40(5):305-311. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25901978

- Lonner BS, Toombs CS, Husain QM, Sponseller P, Shufflebarger H, Shah SA, Samdani AF, Betz RR, Cahill PJ, Yaszay B, Newton PO. Body Mass Index in Adolescent Spinal Deformity: Comparison of Scheuermann's Kyphosis, Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis, and Normal Controls. Spine Deformity. 2015 July;3(4):318-326.

- Lonner BS, Terran JS, Newton PO, Shah SA, Samdani AF, Sponseller P, Shufflebarger HL, Betz RR. MRI Screening in Operative Scheuermann's Kyphosis: Is it Necessary?: PAPER# 70. InSpine Journal Meeting Abstracts 2011 Jan 1 (p. 91). LWW.

- Lonner B, Yoo A, Terran JS, Sponseller P, Samdani A, Betz R, Shuffelbarger H, Shah SA, Newton P. Effect of spinal deformity on adolescent quality of life: comparison of operative Scheuermann kyphosis, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, and normal controls. Spine. 2013 May 20;38(12):1049-1055.

- Papagelopoulos PJ, Klassen RA, Peterson HA, Dekutoski MB. Surgical treatment of Scheuermann's disease with segmental compression instrumentation . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001 May;(386):139-149.

- Tribus CB. Scheuermann's kyphosis in adolescents and adults: diagnosis and management . J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(1):36-43.

- Winter RB, Hall JE. Kyphosis in childhood and adolescence . Spine. 1978;3(4):